It was a cold and snowy January in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan on the eve of my 13th birthday back in the 1960s. Five of us Boy Scouts experienced winter camping for the very first time. We packed in our sleeping bags and other essential gear as we hiked through knee-keep snow to our campsite. During that afternoon, our group built a snow shelter with four walls about chest high, and we left a small opening for a door. Topping off the structure with pine boughs covered with snow for a roof, we were quite cozy for our overnight adventure.

Wilderness survival expert, Tom Brown, Jr. wrote, “I can hardly overstress the importance of shelter. Like your own home, a good one will protect you, maintain your body heat, and provide a place you can identify with.” The quality of a shelter is essential to the enjoyment of a winter camping experience. Since age 13, I have learned a lot about winter camping and snow shelters. Our four-walled shelter back then was adequate and worked well. In my adult years I have been inside an igloo, crawled into a few strangely designed snow-forts and visited a couple other forms of winter shelters. But the most functional and suitable snow shelter that I have slept in quite comfortably is the quinzhee. It is kind of like sleeping in your refrigerator rather than in your freezer.

“Quinzhee,” also spelled “quinzee,” is a snow shelter concept of Native Americans and the First Nations of Canada. In NOLS “Winter Camping” by Buck Tilton and John Gookin, quinzhee was defined as a hollowed –out pile of snow traditionally used by Athabasca natives on the Taiga. Today, the quinzhee is a very popular shelter used by many who enjoy camping in the snow.

The Art of Constructing a Quinzhee

Experts will vary some on the construction of a quinzhee. But when it comes down to the basics of quinzhee building, here is how it all shakes down.

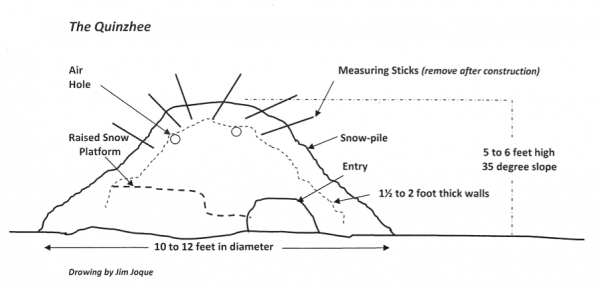

With a shovel, pile snow into a mound about five to six feet high in a circle with a 10 to 12 foot diameter. This size quinzhee should house one or two campers comfortably. The larger the pile the more campers you can fit in it. Poke about a dozen two-foot long sticks into the pile at the top and around the sides. These sticks become guides later on when digging out your quinzhee so that you do not carve too close to the surface. It is difficult to gauge proximity to the outside when inside. Once completed, remove the sticks.

Pack the snow a bit with your mittens or gloves if it is soft snow. Otherwise, let the snow compact on its own. Then let it sit for a few hours. Time and pressure will alter the snow’s density, resulting in compacted snow that will hold up when digging into it later on. The snow must be firm before you can hollow out the quinzhee.

Before deciding where to start digging a door into your quinzhee, decide which direction it should face. The most logical direction if prevailing winds are coming from the west or northwest would be for the door to face east or south to southeast. A southern exposure would allow some sunshine to come in on you in the morning.

Next, dig an entrance low and relatively small, working your way up and then into the mound. I use a heavy metal collapsible shovel to dig out the quinzhee. In order to prevent from putting stress on the walls, be careful and cut small chunks of snow (like sculpturing), and do not pry the snow. You will eventually be digging out a dome-shaped room inside the mound, digging no closer than one-and-a-half to two feet from the surface. The sticks you previously poked into the mound will be your guide, so you keep within that recommended distance. Then, smooth out the surface inside the structure. It should harden nicely.

Keep in mind some laws of physics. First, cold air falls. Have your sleeping area slightly elevated from the floor of your structure so that cold air will fall down from that space. Secondly, by way of conduction, cold from the ground underneath you will pull warmth from your body unless insulated. So, sleep on the elevated platform of snow, and place a tarp on the platform followed by a good insulated sleeping pad. I use two pads; an open cell pad and a self-inflatable pad on top of it. And sleep in a winter-rated sleeping bag wearing warm winter clothing.

Thirdly, an arch will support better than a squared space. In other words, carve out a curved dome-shaped cavern parallel with the curve of your snow shelter, rather than making right-angled walls. And finally, humans need oxygen to breath. It is important that you make three or four adequate size air holes through the roof or wall of the quinzhee. The vents also help body-produced moisture to escape.

Princeton University’s Outdoor Action program has an excellent Guide to Winter Camping site online at www.princeton.edu/~oa/winter/wintcamp. They point out that piling snow for a two person quinzhee (they also refer to it as a “snow mound shelter”) would take two people about an hour. Although I let my quinzhee settle for three to four hours or overnight, Outdoor Action says the minimum time for it to compact naturally is one hour. You reduce the chance of a collapse if you let it set longer. And they also say that a 35 degree angled snow mound is the best angle for snow to settle, since it will reduce buckling of the roof when excavating its interior.

Do not burn lanterns or stoves inside the quinzhee, since they produce carbon monoxide. Use a contained candle and dowse it when going to sleep. And, I recommend keeping a small shovel inside your quinzhee and next to your sleeping bag at night just in case of snow droppings or a cave-in. Your little home away from home is now complete.

First-timers Stay Close to Home

Building a quinzhee is hard work. You will work up a sweat shoveling snow to make an adequate snow-pile for your shelter. And most likely you will get wet from digging out your quinzhee. When you complete your project, I am certain you will be wet, cold and tired. For the beginner quinzhee camper, I recommend building your quinzhee close to home for the first few times. Construct it at home or at a nearby campground where you have access to your car.

Each year for the past several years, I would shovel snow off our deck at home into one big pile. Since our deck is about 10×30 feet, there is ample snow on its surface to make a six-foot high and 10-foot diameter snow-pile needed to build my quinzhee. I had perfected a construction style that was not only great for cold weather camping, but also designed to complement my slight claustrophobia. I do not like tight spaces that restrict me. Therefore, when I dig out my quinzhee, I make sure I have ample room to stretch out when lying down and space to spare above my head when sitting up.

I also make four air holes the diameter of a baseball, and I excavate an extra wide entry allowing me to look out over the entry barrier and see trees and sky. My entry is about twice the size as normally recommended. I then block wind by building a two-and-half to three-foot high curved snow-wall about three feet out from the structure. The wall spans around the quinzhee entryway. And finally, I use a backpack or sled to block the doorway.

At times when I finished making my quinzhee, I would take my sleeping pad, sleeping bag and pillow in hand, say goodnight to my lovely wife Liz and head out the door to sleep in my new dwelling. And each time I did this, she would bid me goodnight by saying in a critical but loving tone, “Your nuts!”

Snowshoeing to Destination Quinzhee

So, how does snowshoeing fit into a quinzhee experience? An exciting adventure is to snowshoe a few miles into a backcountry area carrying your backpack filled with all the essentials you need to spend an overnight in a quinzhee. It provides both a snowshoeing and a winter camping adventure combined.

Paul Petzoldt, founder of the National Outdoor Leadership School once wrote that “winter camping and mountaineering must be near perfect to be enjoyable and safe.” When taking on this level of adventure, it is important to be prepared, skilled and experienced in winter camping before heading out on the trail. Be sure to have the necessary four-season camping gear, including a shovel, tarp, winter sleeping bag, sleeping pad, and extra winter clothing. I also recommend taking along a tent just in case your shelter collapses or you are not able to finish building it. It would add about four or five pounds to your pack.

During a backpacking trip to the Porcupine Mountain State Park in Northern Michigan, I lead a group of college students on snowshoes three miles into the backcountry. Students had the choice of setting up a tent or a tarp shelter with a snow wall, or building a snow shelter. A couple of my more adventurous students built a quinzhee. It was an adventure I am sure they will always remember.

For the close-to-home quinzhee campers, you too can include snowshoeing in your adventure. Following a laborious day building your quinzhee and a restful night sleeping in it, enjoy a snowshoe hike the next morning. I woke up one morning after sleeping in my quinzhee at home, put on my snowshoes and headed out for a most pleasant snowshoe hike alongside a frozen lake and into a nearby forested area.

Regarding my night in the quinzhee, I wrote in my outdoor journal, “It was a beautiful clear-sky night, but cold. The stars were out when I crawled into my quinzhee. I lit my candle and warmed my hands over it for a while. I then blew it out and snuggled down in my sleeping bag. I was surprised, as cold as it was that I did not get chilled at all that night. It was a wonderful night’s sleep. I loved it.”

A fair amount of information in this article is taken from a column I wrote for “Silent Sports” magazine, published by the Journal Community Publishing Group, in February 2012, titled “Quinzhee Construction: Making a Snow Dome a Home.”

Leave a Comment