My great, great-grandmother on my father’s side of the family was Angelique Beaudoin (pronounced bo-d’uah). She was referred to as a “metis,” meaning that her parents were of mixed races. Her father was French Canadian, and her mother was an Ojibwa Native American. That makes me a descendant of the Ojibwa, and because of that lineage, I am interested in Ojibwa history and culture, including Ojibwa snowshoes.

Some of the links in this article may contain affiliate links. When you make a purchase using these links, part of the proceeds go to Snowshoe Mag. Additionally, as an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Please see our disclosure for more details.

About the Ojibwa People

Ojibwa are also called Chippewa. According to information researched by Glenn Welker in “The Indigenous People,” the U.S. treaties referred to the Ojibwa as Chippewa. Drop the “O” from Ojibwa and say both “jibwa” and “Chippewa,” and they sound quite similar… hence the variation in sound from the Native American to U.S. government pronunciation. Historical documents reveal several spellings of Ojibwa, such as Odjibwe, Ojibwag, and Ojibway.

And the name Ojibwa, which means “to pucker,” was given to them by other Native Americans. This name referred to the style of moccasin they wore, with the toes sewn inward to keep the snow out. But the Ojibwa refer to themselves as Anishinabe, a word meaning “original people.” Although I am interested in their linguistics, I am more intrigued by their history, specifically their adaptation to winter using snowshoes. The Ojibwa lived in Great Lakes regions and survived many winters with deep snow.

The Ojibwa Snowshoe

In 1860, Johann Georg Kohl wrote the book Kitchi Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway. He captured many aspects of life at the time. In referencing that which is essential to Ojibwa living, he stated, “This is the snowshoe which is as necessary in winter as the canoe in summer.” He continued, “Through the whole of North America, all the warriors, hunters, traders, travelers, churchgoers, men, women, and children, move about at that period in snowshoes.”

Creating the Snowshoe

In looking at various historical references (including The Crafts of the Ojibwa: Chippewa by Carrie A Lyford), white ash was most often used for snowshoe frames. Strips of green wood were steamed or heated over a fire to soften the wood until it was pliable. It was then carefully bent to the desired shape. Usually, they inserted two cross pieces of wood to strengthen the frame.

The decking was made of narrow strips of rawhide woven together and tied to the frame. Depending on the era, the hide came from moose, deer, elk, caribou, and horse. Lyford wrote that the Ojibwa used a hexagonal weave in the netting of the snowshoe. For bindings, they fastened a piece of leather on the decking where the foot lays, and a leather wrap came across the instep to hold the foot in place.

The Ojibwa woman walked on “Bearpaw” snowshoes. They were short and oval or near-round shoes that were good for maneuvering around the camps and villages. The men often wore long, narrow snowshoes that would provide good tracking (to aid in traveling in a straight line) when in deep snow and out in open fields or the forests as they hunted.

Read More: Traditional Wooden Snowshoes: Shapes, Designs, and Names

A Unique Design

Of significance is that the Ojibwa created their own design for a snowshoe. This design would aid them when hunting on varying terrain of the Great Lakes region.

The snowshoes made for tracking had a long pointed tail and a long pointed turned-up toe. One reason for the front point was so the ‘shoe could slide gracefully through snow and brush that surfaced above the snow. Today this wood-framed snowshoe with points on both ends is called the “Ojibwa snowshoe.”

Johann Geog Kohl wrote, “The nature of the ground to be traversed regulates to a considerable extent the form and size of the snowshoe.” The size would vary depending on their use and terrain. Some were 5 feet (1.5 m) in length or longer and one and a half feet (0.45 m) in width on average.

Read More: A Few U.S. Artisans Keep Traditional Snowshoes a Tradition

Snowshoes in Ojibwa Traditions

An interesting Ojibwa tradition was the snowshoe dance. In an 1835 painting by George Catlin titled Snowshoe Dance at the First Snowfall, the artist depicted Native American hunters wearing snowshoes while dancing around a pair of snowshoes suspended from a tall pole during a snowfall. The dance was in hopes of having a successful hunt during the coming winter season. Snowshoes to the Ojibwa had a significant place in their traditions and history.

In referencing A Dictionary of the Ojibwa Language by Frederic Beraga, “agim” is the word for a snowshoe. Furthermore, “nind agimosse” means “I walk with snowshoes.” Johann Georg Kohl indicated that the Ojibwa name for snowshoe probably came from the word “agimak,” meaning ash wood. As we learned, Ash wood is a common material for most snowshoe frames.

“Nind agimike” means “I make snowshoes.” So, I decided nind agimike in a snowshoe weaving class to get a feel for the Ojibwa snowshoe. I didn’t make the shoe itself, but I weaved the snowshoe deck from a kit.

Read More: A Historical Perspective of Snowshoes

Crafting My Snowshoes

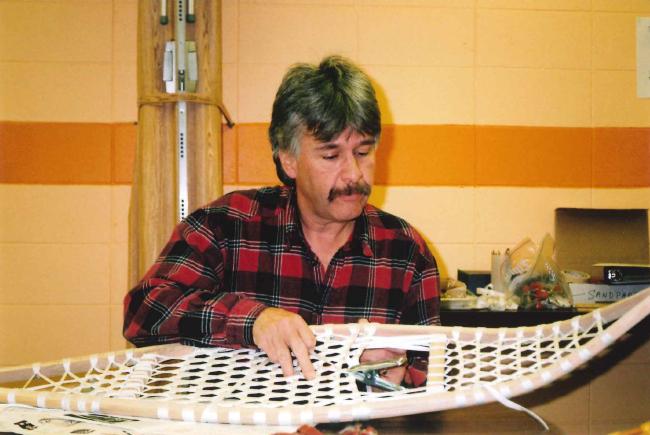

I attended a weekend course at a university environmental education center several years ago. Students had the choice of selecting one of a few snowshoe kits, including Bearpaw, Alaskans, and Ojibwa snowshoes. I, of course, chose the Ojibwa. Country Ways of Wilcox and Williams Inc., a popular traditional snowshoe manufacturing company out of Minneapolis, Minnesota, made the kits.

We began class on Friday evening. The first task was sanding the white ash frames and measuring many feet of tubular nylon lacing. It was not too bad of a start to the course. But by Saturday, I started to question my skills since I spent from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. (with only two half-hour lunch breaks) weaving and having to backtrack when making an error in my pattern. I hate backtracking anything. So it definitely tried my patience.

The instructor would say, “Pay attention to the golden crossover rule.” This rule requires lacing with rights over lefts and under horizontals, lefts over horizontals and under rights, and horizontals over rights and under lefts. I was experiencing a weaving challenge, much less a headache.

After a while, I caught on. By noon on Sunday, I had completed weaving a beautiful pair of Ojibwa snowshoes. Alas, all I had left to do was the varnishing and add on the bindings.

I felt connected to my snowshoes, having had a part in putting them together. I also felt a connection to Ojibwa history by experiencing in a small way what my ancestors may have experienced as they, too, weaved to make their snowshoes. But their weaving was for necessity, whereas mine was for recreation. A vast difference, I realize.

Read More: Making Your Snowshoes From Scratch

No Better Feeling

I took to the Big Eau Pleine Flowage shoreline in central Wisconsin for my maiden voyage. The flowage offered me a wide-open flat terrain with deep snow. Thus, it was exhilarating! I loved the feeling of nearly walking on snow. It is amazing how with all my snowshoeing experience on aluminum frame snowshoes and my traditional Bearpaws, I really have not felt floatation like I did on these larger Ojibwa snowshoes.

I thought about my great, great grandmother Angelique when I listened to the swishing of my Ojibwa snowshoes on a peaceful hike on a secluded Wisconsin or Upper Michigan trail. As a child, she used snowshoes as a way of life. It is conceivable that her Ojibwa grandfather hunted on snowshoes, and her grandmother gathered firewood while the children ran and played games, all on their snowshoes.

And who knows, when hiking on my Ojibwa snowshoes, I may cross paths with one of Angelique’s past paths or those of my other Ojibwa ancestors from centuries ago. I will never know. But it holds special meaning to know that it could happen.

This story is based in part on an article by Jim Joque in Silent Sports magazine, “The Path of Ojibwa Snowshoes,” in January 2006. The current article originally appeared online at snowshoemag.com on March 3, 2012. It was updated on June 29, 2023, to include new information.

Read Next: Traditional Snowshoe Care and Maintenance

Ojibwe is ojibwe and Metis is metis .

Maybe some netis are mixed byt that’s nit what it means .

Metis is own culture in own distinct area.

I still use my Anishinabe snow shoes that I got when I used to go out with an elder friend of mine. On our return he taught me to bang the snowshoes together three times and say “metonka” to them in thanks for getting us home. John is gone now and I sometimes have a hard time convincing my current companions that this is something to believe in. Can anyone back me up? But I don’t really care. I will keep doing it.

Oneida from Sixnay at Ohsweken here…. and I favour my Ojib shoes for much of my snowshoeing adventures!

Thanks to your People and you keeping the tradish alive!

Leaving Tracks: A Maine Tradition is a how to book on making traditional snowshoe

Thanks for the recommendation, Brian!

Where can I fine detailed plans for building my own pair of Ojibwa Snowshoes. i am looking for dimensions lacing techniques etc.

I am looking for a pair of hand made traditional Ojibway snowshoes. I don’t like the traditional style that is sold in the stores. They’re heavy and not shaped very well. Also not made very well either. I really like your snowshoes featured in the above photo. Is it possible to purchace a pair from you 10 – 12″ X 60?

I have made and used Ojibwa shoes lots and are the best I could ever find for hiking in deep powder snow

I share your interest in snowshoing and our Indian heritage. I too am of Ojibwa descent. Although I cannot find a direct lineage to any specific tribe, I am most closely tied to the Turtle Mountain Band. My grandmother was born in northern North Dakota after her family moved down from Canada. She was French Canadian and Ojibwa. My mother was born in 1920 in a small log cabin in the Lake-of-the-Woods area in northern Minnesota where my grandfather was homesteading.