Snowshoe historians can only make an educated guess that the first snowshoe designs for walking atop snow predate the earliest rock art drawing depicting a skier that has been dated to around 6000 BC, and is located in Norway. But, based on the logic that one must learn to walk before one slides, it makes sense that snowshoeing predated skiing as a form of winter mobility.

One theory surmises that the ability to snowshoe actually facilitated the three westward waves of migrations out of Siberia into North America, and the eastward migrations into Scandinavia during the Ice Age. The use and knowledge of snowshoe making between 30,000 and 5,000 years ago, represents a vital advantage for winter travel and hunting, and likely explains evidence of snowshoe designs as far south as New Mexico, and east to Scandinavia.

The most sophisticated early designs were found here in North America, among the Inuit’s from St. Lawrence Island, and with the Chukchi’s just miles away across the Bering Straits, in Siberia. Japanese, Czechoslovakian and Swedish snowshoe examples lean toward more roughly functional and less sophisticated shapes.

French explorer Samuel De Champlain noted in his 1608 travel accounts, having formed an alliance with the Huron and Algonquin Nations, “Winter, when there is much snow, they (the Indians) make a kind of snowshoe that are two to three times larger than those in France, that they tie to their feet, and thus go on the snow, without sinking into it, otherwise they would not be able to hunt or go from one location to the other.”

In 1757 during the French and Indian war, a famous “battle on snowshoes” between Rogers Rangers and the French occurred near Fort Carillon on Lake Champlain. Rogers, and seventy-four Rangers, ambushed one hundred French and Canadian militia. The French noted in their reports afterwards, that they were “…at a disadvantage, since they were without snowshoes” and “floundering in snow up to their knees.” Rogers and his men survived, in no small part due to their superior snow technology.

And at least one present day artist has been inspired by the “Battle on Snowshoes” and the role of snowshoes for winter hunter and trapping, travel and battles, during the development of New England.

And at least one present day artist has been inspired by the “Battle on Snowshoes” and the role of snowshoes for winter hunter and trapping, travel and battles, during the development of New England.

Bronze sculptor Jud Hartmann of Vermont and Maine has created a limited edition series, The Woodland Tribes of the Northeast – The Iroquoian and Algonquin’s that features northeastern woodland natives, as well as early French trappers and English rangers, on snowshoes. The snowshoes he uses as models hang over his fireplace. He said, however, that he was more specifically inspired by the “Tete-de-Boule,” or Attikamek snowshoes whose creation reach beyond craftsmanship to art.

“They have the finest weave,” Hartmann said describing a pair he had seen in Quebec, and was extremely impressed with. “They are not content to just weave (but must also add) a …design,” to the webbing. He notes this finer mesh is for “lighter, fluffier snow.”

From Northeastern Canada to Maine is where the most sophisticated designs were found, and north of Montreal, the neighboring native nations of Wendake and Attikamek Huron’s were the best known snowshoe makers.

From Northeastern Canada to Maine is where the most sophisticated designs were found, and north of Montreal, the neighboring native nations of Wendake and Attikamek Huron’s were the best known snowshoe makers.

According to a report of “the British Association for the Advancement of Science” published in 1900, snowshoe making had become a thriving business concurrent with the north and westward expansion of North America, and would not be delayed by winter.

“Seven thousand pairs of snowshoes were turned out at Lorette (now Wendake) in 1898; but the demand was larger than usual that year consequent on the opening of the Klondike. That same year as many as 20,000 (cow) hides were dressed in the locality and 12,000 dozen pairs of moccasins manufactured.” The report notes a sharp drop off of demand for the Lorette snowshoe the following year as “…the Lorette snowshoe (was) found (not to be) of as suitable a shape as other makes for the use in the Klondike.”

The report goes on to note that the art of snowshoe making remained largely a Huron industry, and very few French Canadians were trained in their construction.

According to the Attikamek tradition, aesthetics are as important as the function in the bent wood shape of the snowshoe. One could imagine that even the tracks left behind in the snow would be considered when thinking about the design.

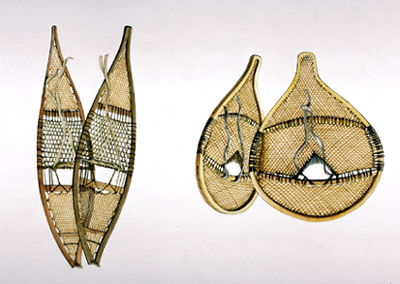

GV Snowshoe’s history page asserts, “To the south, the front of the snowshoe was often bent in the ‘square toe’ pattern and, in some areas, further hollowed along the sides to enhance the overall effect; farther north, snowshoe tails were given the rounded or square-ish forms known as the ‘beavertail’ style.”

Noting the greater amount of labor involved in the latter, “…greater care was expended in their weaving, as the most complex woven designs can be seen in these snowshoes.” And it seems that while the men bend and bound the frames together, the webbing was primarily a woman’s contribution. “Here the women expressed their talent by incorporating beautiful geometric patterns

in a mesh that was sometimes so closely woven that a matchstick would not pass through,” the GV account says.

Northeast Native Snowshoes After the 1940s

Author and early researcher in birch bark canoe building, and almost incidentally, snowshoe making, Henri Vaillancourt (“Making the Attikamek Snowshoe” at www.birchbarkcanoe.net) of New Hampshire, spent time with the Attikamek’s (as well as Cree and Algonquin) in the 1970s and 80’s. He worked with them for about ten years studying canoe-building and snowshoe making.

Vaillancourt said he saw about six or seven types of snowshoe variants from tribe to tribe. Snowshoe making “…was well practiced among the Cree in the 1970s and 1980s,” Vaillancourt said. But even then “…refined snowshoe making was rare at the time we were there.”

Vaillancourt noted that the Algonquin, Cree, Montagnais and Attikamek are related peoples who, over time have intermarried, so they are “…culturally very, very similar. All throughout modern history, you see the (similarity) in techniques and forms of decorations. All of these tribes use woven decoration in the toe and tail weave.” The differences lay in style and the complexity of designs.

But individual preferences still existed. At the time, he said, “There (were) certain things that the Attikamek (did) that I (did not see) the Cree or the Montagnais do,” Vaillancourt said.

Vaillancourt said the aesthetic aspect of snowshoe making was important. “They’re the experts when it came to that. The artistic aspect of it is what is most attractive,” to the makers.

“The woven designs called ‘mazin haban’ (in Attikamek, and ‘mashin haban’ in Cree) refers to …decoration…woven into the snowshoe,” he described. He noted there are those who “… will paint the entire weave such as the Cree.”

Vaillancourt said the weaving of designs into the webbing is more often than not “women’s work. The men sometimes do the midsection but not all the men do that. Most men don’t know how,” however.

In contrast, the “…practicality of a modern snowshoe is not anywhere near as effective on snow.” He wagered that anyone on modern snowshoes “would not be able to keep up with a native (moving) side by side in the environment of broken snow. They would quickly be left behind – there is no way they would be able to keep up. They would quickly become exhausted.”

Modern snowshoes may be designed to be light weight and aerodynamic, but they are not very practical off packed trails as the surface area is predominantly too small. For long distances, or use in hunting or trapping, they are far less efficient.

On traditional snowshoes, the experience is “…quite the opposite. The designs are very sophisticated, and designed for the purposes of what it was intended” to be used for. “The (Northeast tribes) were hunter gatherers and (snowshoes) had to be light …in order travel over new snow.” They were designed for “floatation and lightness and not carrying more weight on their feet than they absolutely had to.”

Vaillancourt said there were “Three basic types – long and narrow snowshoes, very wide and short snowshoes, and an intermediate (style) between these two.” He noted that neighboring Wendake and Attikamek’s shared similar types of intermediate style snowshoes with the Algonquin, Ojibwa, Micmac, and Wabanaki tribes of southern Quebec, Maine and the Maritime provinces.

There were many variants in style that depended on the tribal group, and even within a tribal designation within different bands.

The difference among individual makers lay mostly “… in terms of proportioning of the front and back section in relation to each other. The square inches of flotation makes a huge difference in terms of how it walks,” Vaillancourt pointed out. “If it’s wider in front, the front stays up. If it’s narrower (in front), it cuts down evenly with the back (into the snow).”

“The Attikamek used the square toed snowshoes like the Huron …a wide-ish snowshoe but not as long. The eastern Cree used long and narrow snowshoes in western Canada as well as the wide snowshoes of the Montagnais.”

However, Vaillancourt said, overall, it was more about “…what you get used to. There is no consensus (on which styles were used for what purpose). It was individual preference. There is no truth” to using specific styles for specific snows or purposes.

However, Vaillancourt said, overall, it was more about “…what you get used to. There is no consensus (on which styles were used for what purpose). It was individual preference. There is no truth” to using specific styles for specific snows or purposes.

He said the longer snowshoes used among the eastern Cree and Ojibwa’s were “…used for exactly the same purposes as the wide snowshoes. The eastern Cree were the only group that used both the long and narrow, and short, wide snowshoes, though they originally only used the wide snowshoes until the 1940s.” He said at some point, “…the long snowshoe was introduced from the west and started to make inroads into the eastern Cree.” And there, Vaillancourt said, he saw “some individuals use both.”

“Generally speaking, for fast walking on long trips, they had a tendency to use the long snowshoes. To just work around camp, they used the more rounded ones. Some people would not switch from one to the other and in general were able to keep up one with the other,” Vaillancourt described.

Even with the big round snowshoes, you “…don’t have to walk …splay legged. The snowshoes pass over each other. When they are standing in place, they stand with one snowshoe over the other.”

And no one seemed to trip. “When you are walking on snowshoes that are two feet wide, the center of spread where the feet are enough (about 12 inches) so it clears without hitting the other ankle.”

And no one seemed to trip. “When you are walking on snowshoes that are two feet wide, the center of spread where the feet are enough (about 12 inches) so it clears without hitting the other ankle.”

He noted that snow conditions in the fall and spring versus midwinter did determine different snowshoe use, however. The size and weight of the snowshoe was determined by the type of snow conditions.

“Midwinter snowshoes were very finely woven for maximum floatation and maximum speed. A smaller and more coarsely woven snowshoe was chosen for springtime. They were not wasting (all the time and effort of the finer woven snowshoe) on spring time conditions. You’d wear it out. You don’t need as big a snowshoe in the fall and spring so they were smaller because you don’t need that sort of surface area. They were quite a bit smaller by about a third with a more open weave,” Vaillancourt noted.

Tradition Today

Today, the sport of snowshoeing has expanded into an alternative winter sport for those who like to run… on snowshoes, and for those who prefer to get out on top of the snow in a more sedate, quieter ambulation that alpine or cross-country skiing.

Snowshoe designs and manufacturers cater to the demand and, like GV Snowshoes (www.gvsnowshoes.com), located in Wendake just east of Quebec, home of the Wendat-Huron reserve center, some continue to make traditional style snowshoes from designs evolved out of native origins.

However, the demand for the traditional snowshoe is largely outstripped by demand for modern smaller, lighter, fabricated styles mainly used for running races on packed snow.

Still, at almost every event, some traditional style of snowshoe can be found. And there are some snowshoers who still prefer the traditional designs as GV Snowshoes notes. GV continues some of the traditional Attikamek snowshoe designs, according to Patrick Morency, GV director of development, and comprise about 5 percent to 8 percent of their sales.

did you ever hear of w h ketchum swowshoe co in grayville Vt.

[…] Art and History of Snowshoe Making in the Northeast […]