Sometimes, when I’m in a delusional mood, I think I’m a pretty rugged guy. I’ve done a couple of triathlons, ran a marathon or two, gone winter camping when it was below zero Fahrenheit. But when I recently read about the 104th New Brunswick Regiment of Foot I realized I am really, really soft. I am truly a marshmallow.

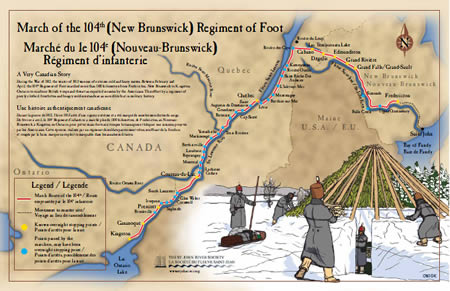

The 104th snowshoed 700 miles in about 35 days, carrying or pulling their supplies and equipment. They did this in one of the coldest and snowiest winters on record. Their orders were to march from Fredericton, New Brunswick in eastern Canada to Kingston, Ontario to help protect that city from the expected American attack during the War of 1812.

The War of 1812 officially began on June 18, 1812 when the U.S. declared war on Britain. The main military objective of the American government was the annexation of the British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, areas that are now Ontario and Quebec. (Canadian Confederation wouldn’t happen until 1867).

There were several reasons that the young country of America felt war with Britain was justified and necessary. The first was a series of trade restrictions Britain instituted to hinder trade between the U.S. and France. Britain was in the midst of a two decade war with France and was trying to deny supplies to their perennial foes.

In order to keep their ships manned, the British navy began pressing men into the navy. Britain did not recognize British immigrants to America as anything but still British. Because of this policy a lot of naturalized American sailors got pressed into service aboard British warships. In fact, Britain wasn’t too strict on whether the sailors they pressed into service were actually British at one time or not. You could say that Britain had an official policy of kidnapping citizens of others countries.

Also at this time Americans were moving into the interior of the country, displacing aboriginal people. In the ensuing violence, the Americans believed the British were arming the aboriginal people and encouraging them to resist the American settlers.

For these reasons the U.S. felt that Britain wasn’t recognizing American sovereignty and that war was necessary.

In the early part of the war things were not going well for Britain. The majority of British troops were already fully engaged in Europe in the war against France. Thus the order was given for the 104th to make their way from New Brunswick to help reinforce the troops at Kingston and since it was February and the rivers were frozen and travel by ship was impossible. They would have to march.

And march they did, with more than 570 men leaving the barracks in Fredericton between Feb. 16 and 21 and heading up the St. John River. Their marching started each day just after first light and continued until about 2:30 p.m. when they would stop and make camp. If they were lucky, they would be able to find accommodations in barns or other buildings. If not, they had to build temporary huts by using their snowshoes to shovel the four or five feet to the ground, then propping small trees around the low snow wall to form a roof frame. Pine boughs were then placed on this to form a roof. In the middle of this hut was a fire pit. Their mattresses were more pine boughs. While some of the men were building the huts, others were getting fires going to thaw out their supper of pork and biscuits.

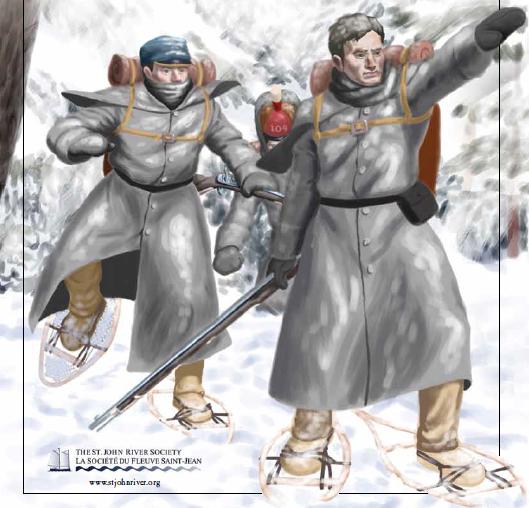

The marching was hard going, especially given that the winter was especially cold and snowy. Every two men were issued a toboggan to carry their gear and up to 14 days provisions. The man in front would pull the toboggan and the man in back held a stick that was attached to the back to help push or hold it back on the downhills. Each pair of men took their turn leading for 10 to 15 minutes to break trail, then they would stand aside to let the regiment pass and rejoin the rear.

Even though each man was required to carry their own gear on the toboggan it really wasn’t that much. Everyone was issued a rifle with 30 rounds of shot, a pair of snowshoes, moccasins, one blanket, a fur cap, mittens and a scarf along with their uniform and greatcoat along with 14 days of provisions. Lieutenant Rainsford of the 104th described their clothing as “poor and scanty, their snowshoes and moccasins miserably made; even their mitts were of poor, thin yarn.” The previous summer an American privateer captured new uniforms destined for the 104th so what they were wearing was old and tattered.

The first section of the route of the 104th was what was called the Grand Communications Route which was up the St. John and Madawaska rivers, on to Lake Temiscouata, overland to the St. Lawrence River and then on to Quebec City. They stayed in Quebec for two weeks before continuing along the St. Lawrence to Kingston at the eastern edge of Lake Ontario.

The records of the march are conflicting but it appears that of the 570 or so soldiers who started the march, only three did not finish. One died on route. Another was left behind with an escort because of severe frostbite. But that’s not to say that they were in great shape at the end. Frostbite was common.

Another ailment many of the men suffered from was mal de raquette which is an inflammation of the Achilles tendon caused by spending too much time on snowshoes. Although the records don’t tell us how many, one of the commanders reported that many had died after the march and many more were sick in the hospital. Those that were healthy enough went into battle in the spring. For enduring these hardships a private in the 104th regiment would earn the not so princely sum of 18 pounds and five shillings per year. For comparison a farm hand at the same time would earn in the vicinity of 30 pounds annually.

During the first stage of the march the men were making from 15 to 22 miles per day or two to three miles per hour. While this may not seem fast it really is incredible. These men were doing this march in hardwood and rawhide snowshoes. Equipment that was a lot heavier than my aluminum shoes. Winter in this part of Canada can be pretty brutal but by all accounts 1813 was a particularly bad winter.

The snowfall was reported to be heavier than in the previous nine years and it was cold, with the mercury dropping to -27degrees Fahrenheit on one occasion. And there wasn’t any down filled clothes at that time. They had to stay as warm as they could in woolen overcoats and thin mittens. And the nights wouldn’t have been any more comfortable. One wool blanket was what each man was issued. And we all know that food is our fuel. I doubt that the calorie count of their daily ration of one pound of pork (including bones) and 10 ounces of biscuit washed down with tea, coffee or hot chocolate would have supplied enough energy to satisfy their requirements.

Yes, these men were tough. So the next time you are debating going snowshoeing because it’s too cold or windy or maybe you don’t have the right clothes. Or you back out of an overnight trip because all you have is a three season tent or your mummy bag is only rated to -15, think of the 104th and get out there and enjoy whatever the weather gods throw at you.

Nice piece on some tough Canadians! As you are out in NB, you probably already know that we are recreating the entire march to Kingston. Time to test your softness?