Understanding El Niño and its effect on snowfall in North America

El Niño is a massive atmospheric-oceanic interaction over and in the Pacific Ocean. It tends to cycle between neutral, positive, and negative conditions every five to seven years.

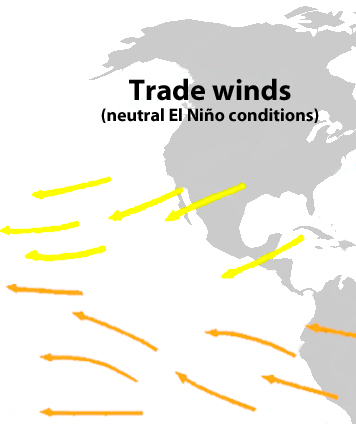

During neutral El Niño conditions, the Walker circulation prevails, and:

- Trade winds blow southeasterly from the coast of North America and northeasterly from the coast of South America to meet near the equator and assume a westerly path.

- The westerly winds push warm surface water in the same direction, and…

- …off the coast of South America, the space vacated by the warm water is assumed by cooler, uplifting water.

- …the warm water accumulates in the western Pacific.

- In an atmospheric/oceanic relationship,

- the air above the cool waters in the eastern Pacific cools, thereby becoming denser. The dense air sinks, leading to high surface air pressure.

- the air above the warm waters in the western Pacific warms, thereby expanding. This air rises, leading to low surface air pressure.

Under neutral El Niño conditions, the trade winds blow from the coasts of the Americas towards the equator. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

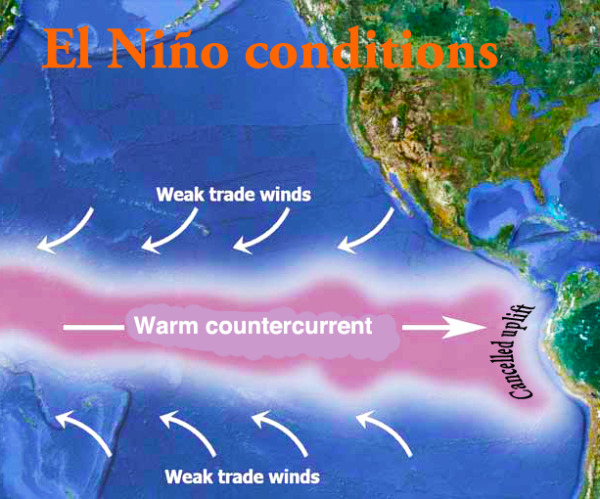

During positive El Niño conditions, the Walker circulation weakens or even reverses. This has an effect on the Pacific and Polar jet streams, which can lead to atypical winter temperatures and precipitation across North America.

What do El Niño conditions mean for North American snowfall?

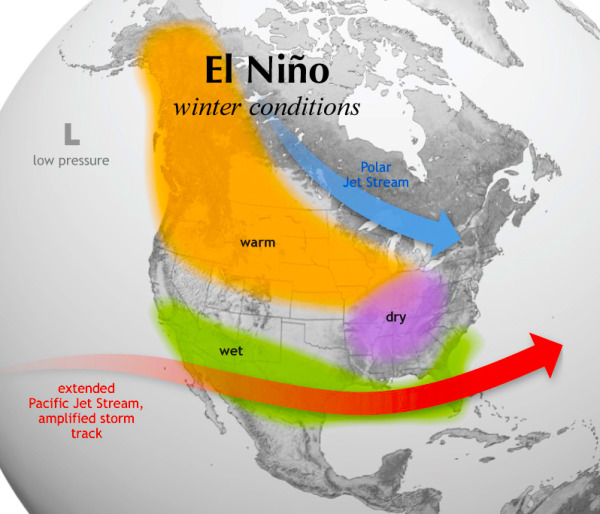

El Niño conditions during North American winters tend to, with the emphasis on tend, result in predictable temperature and precipitation patterns on a region by region basis.

The Southeast tends to experience cooler, wetter winters and thus the potential for more winter storms. In the Northeast, strong El Niño conditions can be counted on to result in unusually snow dry conditions. Weak El Niño conditions can be another story. While the average winter temperature can be somewhat warmer than usual, it is not uncommon for multiple winter storms to track up from the Southeast.

El Niño’s effects on winters in the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic seem to be less consistent than in other regions. It does seem to often to be the case that the Ohio Valley and lower Great Lakes tend to experience drier, warmer than usual seasonal conditions during El Niño winters. This means light snowfall across much of the Midwest and mild conditions for Chicago.

The uplands of Southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico tend to experience above average snowfall during El Niño winters.

The mountain and interior Pacific Northwest tends to see less snowfall under El Niño conditions as temperatures are typically a bit warmer than usual and the Jet Stream has directed moisture towards the coast of California.

El Niño forecast for the coming weeks

Reading signs of emergent positive El Niño conditions is iffy at the best of times, but this year has proven especially dicey.

In April the online science writers were drawing clicks with talk of the possibility of a “monster” El Niño for the coming winter comparable to the massive 1997 El Niño. By June this talk had turned to head-scratching over the disappearance of the early spring signals of a strong El Niño.

By early September came word that the “stalled El Niño is poised to resurge.” On October 9 the Climate Prediction Center called for a 60–65 percent chance for the development of a weak El Niño. In the latest CPC prediction the likelihood has been dropped to 58 percent.

As the solstice nears, my 2014/2015 snow play looks less and less threatened in southern New England, as does the seafood catch off the coast of South America. But both I and the fisherman will be keeping our fingers crossed.

References

Dawson, Alastair G., and Greg O’Hare. 2000. Ocean-atmosphere circulation and global climate: the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Geography 85(3):193–208.

Hunter, Thad, Glenn Tootle, and Thomas Piechota. 2006. Oceanic-atmospheric variability and western U.S. snowfall. Geophysical Research Letters 33(13):L13706. doi:10.1029/2006GL026600.

Philander, S. George, ed. 1990. El Niño, La Niña, and the southern oscillation. Vol. 46 in International Geophysics Series. San Diego: Academic Press. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780125532358.

Trenberth, Kevin E. 1997. The definition of El Niño. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78(12):2771–77. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)0782.0.CO;2.

Author information

May I use an image in this for a community magazine in Scotland trying to explain the unusual rain falls and floods we are suffering?

I don’t have any problem with your doing so. Would you mind linking the image back to this post?